Fraudulent activities committed by employees, managers, and even executives can severely damage a business both financially and reputationally. The scope of this problem is typically underestimated, as the idea of team members stealing from the team is unpleasant to consider, much less to discuss out loud. The resulting silence surrounding this issue leads many to assume that it must not be a common problem.

Yet internal fraud causes serious harm to many companies, including (but not limited to) reputational damage, impact on other group companies, disgorgement of revenues or profits, legal fees and fees to consultants, arrests of individuals, fines for individuals, and corporate fines and penalties. This harm is magnified when steps are not taken to either reduce or mitigate its occurrence.

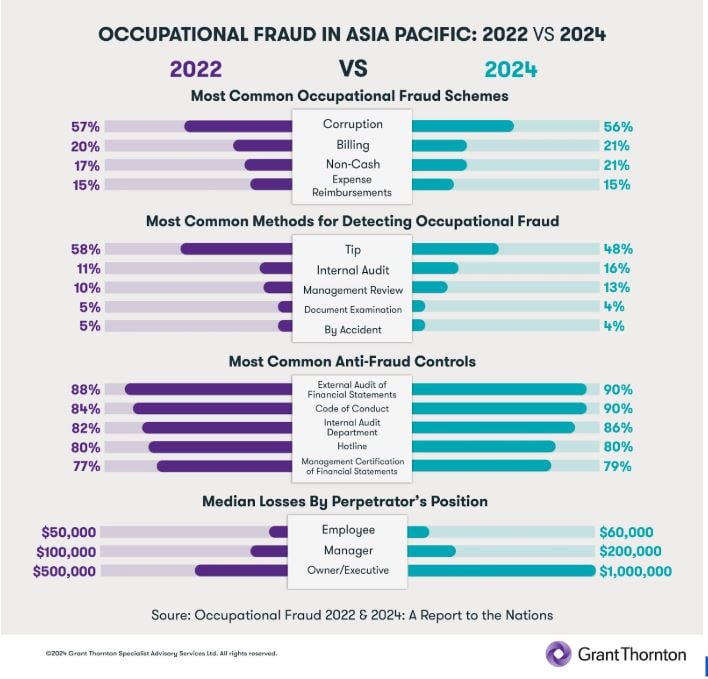

The statistics are sobering. A 2024 study by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners estimates that organisations worldwide lose around 5% of their total revenue due to fraud alone. Among the cases of fraud studied in Asia-Pacific, the median loss due to fraud was $200,000. Those lost assets were fully recovered just 10% of the time, while nearly 30% of the time a partial recovery was made. In the remainder of cases — more than 60% of them — no recovery of lost assets was achieved.

Internal fraud typically involves one or more of the following: corruption (including conflicts of interest, bribery, and illegal gratuities), asset misappropriation, billing fraud (such as revenue leakage or fabricating sales or profits due to KPIs), noncash theft (including inventory, equipment, or services), expense reimbursement fraud, and payroll fraud. The reality is that wherever money or other assets can be skimmed from an organisation, those with access may be tempted to do just that.

Pertinent Examples

Internal fraud was a primary cause of the Bangkok Bank of Commerce collapse in the 1990s. With senior executives involved in embezzlement and unauthorised lending, the bank’s misappropriated funds generated scandals that ruined the reputation of the bank itself — as well as Thailand’s entire banking sector.

In the UK, Barings Bank similarly collapsed in the 1990s due to internal fraud. In this instance, however, the fraud was carried out by one rogue employee who carried out unauthorised trades and hid the losses that they incurred.

In more recent years, several prominent companies in Thailand have experienced significant financial losses due to internal fraud. In one case, a senior manager manipulated financial records to divert funds, causing severe cash flow issues that were only discovered during an external audit. Another organisation faced legal challenges after an internal investigation uncovered a scheme in which multiple employees colluded to inflate supplier invoices, skimming off excess payments for personal gain. Both cases illustrate the continuing risk of fraud even in highly regulated environments.

As these examples demonstrate, even a small number of bad actors can sink an entire organisation. In many cases, upper management is entirely unaware that a problem even exists, until that problem gets out of control. Often the employees who carry out fraudulent schemes are in a position to falsify the paperwork surrounding them, making timely detection impossible without proactive controls in place.

Leadership and Responsibility

Clearly, the frequency and severity of such cases necessitate robust detection and prevention mechanisms. Effective initiatives include anti-fraud training and awareness programmes to encourage the reporting of fraud committed by colleagues or superiors; fraud risk assessments; AI-driven anomaly detection algorithms; separation of duties and responsibilities; and the clear and comprehensive enforcement of anti-fraud policies.

At the same time, companies should recognise their vulnerabilities. Though switching to digital operations across the board brings numerous benefits, it also carries risks. Numbers in a computer database are more vulnerable than traditional and hands-on forms of record keeping.

Moreover, in regions like Asia-Pacific, the prevailing cultural norms may be such that employees hesitate to report on the suspicious behaviours and activities of colleagues. Your business would therefore be wise to stress the fact that tips regarding internal fraud can be submitted anonymously. Approximately 42% to 43% of fraud cases globally are reported through whistleblower or speak-up channels, whereas in Asia-Pacific, the rate is around 58%. It is also worth pointing out that fraud hurts the entire team, that whistleblowers receive protection, and that integrity is a core value of the organisation.

The faster that fraud is detected and rooted out, the less damage the perpetrators can do, and the less emboldened future fraudsters will be.

As mentioned above, organisations in the Asia-Pacific region typically recover only 10% of assets lost to fraud, with more than 60% of cases resulting in no recovery at all. In addition, the median cost of fraud in this region has surged, especially at the executive level, where losses now reach $1 million per case. As shown in the image below, the data from a 2022 study provides a benchmark for comparison, highlighting trends and changes in occupational fraud across the region.

By confronting this issue assertively and comprehensively, your company can better secure its existing assets, and focus on achieving healthy growth within its market.

Grant Thornton can provide independent audits, risk assessments, and other pertinent services to combat internal fraud. Protecting your company assets is the most fundamental element of business security, and it’s never too early to get started.

Note

This article is part of an ongoing series entitled 6 Ways Your Business Can Fail: A Guide to Recognising and Avoiding and Avoiding Critical Threats to Your Company's Success

To read the next article in the series, click here

To read the previous article in the series, click here

To download the full series as a report, click here